Table of Contents

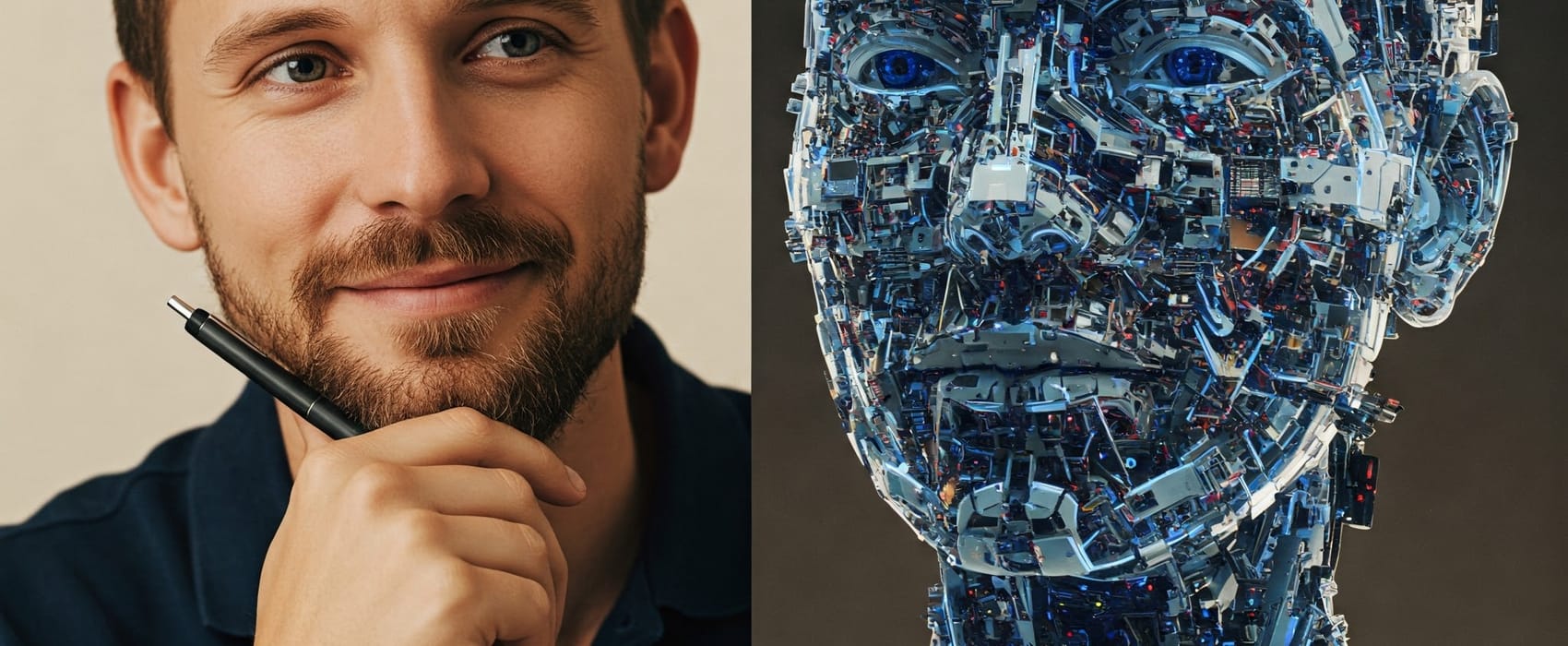

The question of who writes the better texts – humans or artificial intelligence – is becoming increasingly pressing. As Doris Weßels aptly notes, the answer “becomes more and more difficult when we look at the ‘competitor’ AI, which seems to stop at no literary genre, including scientific publications.” [1] Recent developments underscore this: reports of new AI models from OpenAI that are particularly good at creative writing [2, 3] or the “AI scandal” in Estonia, in which an AI-generated text won an essay competition [1, 4], show how far the technology has already developed. Even in scientific publishing, we are entering a “new era” with tools such as STORM or the deep research offerings from Google and OpenAI [1].

The real question: a question of technology?

In view of this progress, I would like to put forward the thesis that the question of who formulates the “better” text is no longer effective in its classical form. If we understand text as “techne” in the ancient Greek sense – as technical implementation, as technical ability to formulate – then we have to recognize that technology, AI, is already superior to us in many areas or is rapidly catching up. Comparing the quality of craftsmanship alone is becoming increasingly obsolete.

Hans Jonas formulated it in “The Imperative of Responsibility”: “By the nature and sheer magnitude of its snowball effects, technological power propels us forward toward ends of a kind that used to be the preserve of utopias.” (p. 54) [5]

This technological power is now also manifesting itself in writing. It overtakes us in speed, in access to information and often also in stylistic adaptability. As Weßels notes, AI is disrupting the “entire process of scientific publishing through the worldwide and usually VERY non-transparent use of AI” [1].

The new benchmark: the personal point of view

If the technical superiority of AI is at least within reach or already exists, what is left for human writing? I argue that we need new parameters for evaluating textual work. The decisive factor will increasingly be the personal “point of view” (PoV) of the author: What does this specific person tell us from their unique perspective, shaped by their experiences, emotions and individual thought process?

This stands in contrast to a development hinted at in the FAZ: “The further we advance into the digital age, the more interest in the specific other person is lost.” [4] Perhaps the emphasis on the authentic human PoV is precisely the answer to this. Ingmar Bergman's belief in the eternal “human interest in humans” [4] could find new meaning by focusing on the distinctive in the human perspective. In the Estonian essay competition, it was significantly “not a breathing human being, but a hastily created digital construct” that formulated concerns about the future [4]. The way it was formulated, the horizon of experience behind it, was missing.

The value of human dialogue and organic development

What fundamentally distinguishes this human PoV from an AI-generated perspective? It is the dialogical character in the broadest sense. A conversation with an AI can be informative, based on huge amounts of data (sometimes accurate, sometimes hallucinated). What it lacks, however, is the sensual, emotional and holistic level.

In a human-to-human dialog, we experience more than just words. We perceive emotions, see facial expressions, feel the atmosphere. We can often follow the development of a thought as a “holistic organic process” – an interweaving of logic, feeling and physical expression. It is precisely this organic development, this struggle for formulation and insight, that characterizes the human PoV. It may not have the comprehensive breadth of an AI, but it has a depth and authenticity that arises from a lived, felt existence. It is more “holistic” in its anchoring in the human condition.

Challenge for science

This represents an immense challenge for science in particular. The scientific ideal traditionally strives for objectivity and a neutral, observational perspective. How can a “personal point of view” find a place here without compromising scientific methodology? But precisely this is one of the central tasks: to find ways in which the distinctive human perspective – that of the researcher – can be integrated into scientific discourse without compromising scientific quality. It is not about subjective arbitrariness, but about recognizing that scientific knowledge also passes through a human filter and that this filter itself is part of the knowledge-building process.

Conclusion

The debate of “man vs. AI” in writing is shifting. Technical perfection alone is no longer the main focus, because here AI is catching up or has already caught up. The future of valuable human writing lies in its uniqueness – the personal point of view, drawing from the depth of human experience, emotion and organic thought development. It is about focusing on the human-to-human dialogue and cultivating the qualities that distinguish us from machines: our lived perspective, our capacity for empathy, and our holistic understanding of the world. The real art will lie in making this human essence visible and tangible in the text.

References

[1] Weßels, Doris. LinkedIn Post. [https://www.linkedin.com/posts/doris-weßels-66a47711_kish-activity-7310666247011028992-CULl?rcm=ACoAAAVCzTgBWFn53SW-xM_TbZyDjpXVO9NltbM] (accessed on 31.03.2025)

[2] The Guardian. "ChatGPT firm reveals AI model that is 'good at creative writing'". [https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2025/mar/12/chatgpt-firm-reveals-ai-model-that-is-good-at-creative-writing-sam-altman] (accessed on 31.03.2025)

[3] Weßels, Doris. LinkedIn Post, Bezug auf The Guardian vom 12. März. [https://www.linkedin.com/posts/doris-weßels-66a47711_kish-activity-7310666247011028992-CULl?rcm=ACoAAAVCzTgBWFn53SW-xM_TbZyDjpXVO9NltbM] (accessed on 31.03.2025)

[4] Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. "Nur die Maschine versteht uns noch". [https://www.faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/medien-und-film/ki-gewinnt-essay-wettbewerb-in-estland-110376583.html] (accessed on 31.03.2025)

[5] Jonas, Hans. Das Prinzip Verantwortung. Suhrkamp Verlag.